N-Forms and Tensors on Manifold

Posted: August 21, 2018

Edited: December 11, 2018

Status:

Completed

Tags :

One-form

Differential-Forms

Tensor

Topology

Categories :

Topology

In this post, Einstein summation rule is used. We are going to generalize the concept of vectors and one-forms to tensors and differential forms (or $N$-forms). This post follows Nakahara.

Tensors

Tensor is a direct generalization to the concept of vector and one-form. A vector takes in a one-form and spits out a number. A one-form takes in a vector and spits out a number. A tensor takes in several vectors and one-forms and spits out a number. A tensor is written as

\[T=T^{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}_{\phantom{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}\nu_1\cdots\nu_r} \Partial{}{x^{\mu_1}}\cdots \Partial{}{x^{\mu_q}} \d x^{\nu_1} \cdots \d x^{\nu_r},\]where there are $q$ slots for one-forms and $r$ slots for vectors, such that

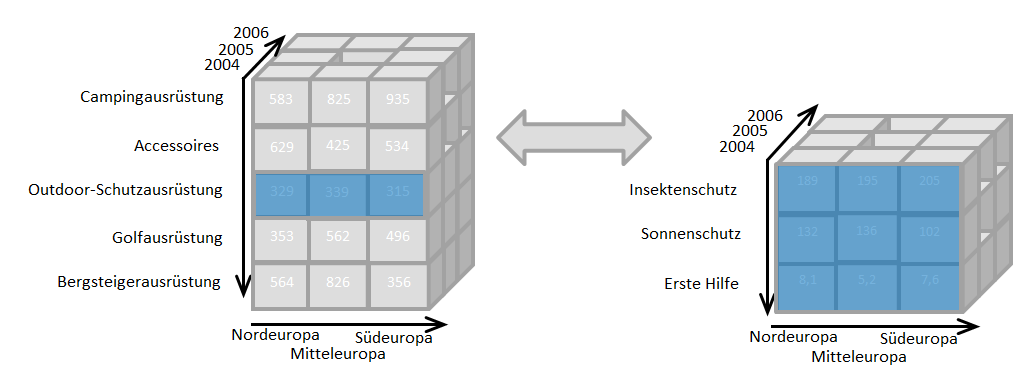

\[\begin{align*} T(\omega_1,\cdots,\omega_q; V_1,\cdots,V_r) & = T^{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}_{\phantom{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}\nu_1\cdots\nu_r} \left(\Partial{}{x^{\mu_1}}\cdots \Partial{}{x^{\mu_q}} \, \d x^{\nu_1} \cdots \d x^{\nu_r}\right)(\omega_1,\cdots,\omega_q; V_1,\cdots,V_r)\\ &=T^{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}_{\phantom{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}\nu_1\cdots\nu_r} \Partial{\omega_1}{x^{\mu_1}} \cdots \Partial{\omega_q}{x^{\mu_q}} \, \d x^{\nu_1}(V_1) \cdots \d x^{\nu_r}(V_r)\\ & = T^{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}_{\phantom{\mu_1\cdots\mu_q}\nu_1\cdots\nu_r} \lbrace\omega_1\rbrace_{\mu_1} \cdots \lbrace\omega_q\rbrace_{\mu_q} \lbrace V_1\rbrace^{\nu_1} \cdots \lbrace V_1\rbrace^{\nu_r}. \end{align*}\]Such tensors are called of type $(q,r)$. $T_{(1,1)},\, T_{(2,0)},\,T_{(0,2)}$ can be written as matrices, while it takes a third dimension to write tensors like $T_{(3,0)}$ in the similar fashion. Below is a diagram from Wikipeida, showing an example of some kind of $3$-d matrix.

Wedge Product

One way to generalize one-forms to differential forms (or $N$-forms) is to take products of one-forms. A two-form can be seen as a “product” of two one-forms. An $N$-form is then a series of a product of one-forms. This product is called a wedge product.

Wedge Product of General Vectors

We will first see how wedge products work in the context of vectors.

The cross product of vectors $U \times V$ is a handy operation in $3$ dimensional geometry. It determines the area of the parallelogram containing these vectors and the plane containing it. A wedge product is the analog used to identify a high dimensional parallelogram.

The wedge (楔) product (楔积) $\wedge$ is a special kind of tensor product.

\[V^{\mu _ 1} \wedge V^{\mu _ 2} \wedge\cdots\wedge V^{\mu _ r} = \sum _ {P\in \mathbb S _ r} \operatorname{sgn}(P) V^{\mu _ {P(1)}} \otimes V^{\mu _ {P(2)}}\otimes \cdots\otimes V^{\mu _ {P(r)}} \label{wedgeDef}\]For example,

\[\begin{align} U \wedge V &= U \otimes V - V \otimes U\\ U \wedge V \wedge W &= U \otimes V \otimes W + W \otimes U \otimes V + V \otimes W \otimes U \notag \\ &- U \otimes W \otimes V - W \otimes V \otimes U - V \otimes U \otimes W \label{wedgeExample} \end{align}\][John] There is a norm for a wedge product (seen as a bi-vector) defined as

\[\begin{align} \norm{A \wedge B}^2&\dfdas(A \wedge B)\cdot(B \wedge A)\notag\\ &=-(A \wedge B)^2 \end{align}\]CONNECTIONS TO GEOMETRIC ENTITIES:

Analogue to cross product as a test of collinearity: The wedge product gives a simple way to test for “coplanarity” or linear (in)dependence of vectors: if $U$ and $V$ are collinear, $U\wedge V=0$.

\[U \wedge V =U \wedge aU=a(U \otimes U - U \otimes U)=0 \notag\]If $W$ is coplanar with $U$ and $V$, $W = a U + b V$, i.e., $U,\, V,\, W$ are not maximally linear independent, then

\[W \wedge U \wedge V = aU \wedge U \wedge V+bV\wedge U \wedge V = 0 \notag\]Analogue to cross product as a indicator of orientation: If $n\gt 3$, there are infinitely many directions perpendicular to the two vectors, so you can’t think of the orientation as a vector (like the cross product in three dimensions). Instead, you may think of the orientation as a circle in the plane of the two given vectors $U$ and $V$, with a direction attached to it in one of the two possible ways: $\circlearrowleft$ or $\circlearrowright$. This orientation is

Analogue to cross product as a way to compute “area of parallelogram”: For two vectors $U=(a,b,c)$ and $V=(d,e,f)$, We can see that the nonzero entries of wedge product are basically the same as for the cross product.

\[\begin{align} \vec{u} \wedge \vec{v} &=(u _ 1,u _ 2,u _ 3)\wedge(v _ 1,v _ 2,v _ 3)\notag\\ &=(u _ 1,u _ 2,u _ 3)\otimes(v _ 1,v _ 2,v _ 3)-(u _ 1,u _ 2,u _ 3)\otimes(v _ 1,v _ 2,v _ 3) \notag\\ &\substack{\text{the basis is different}\newline\neq} \begin{pmatrix} 0 & \red u _ 1v _ 2 − u _ 2v _ 1 & \red u _ 1v _ 3 − u _ 3v _ 1\\ \blue −u _ 1v _ 2 + u _ 2v _ 1 & 0 & \red u _ 2v _ 3 − u _ 3v _ 2\\ \blue −u _ 1v _ 3 + u _ 3v _ 1 & \blue −u _ 2v _ 3 + u _ 3v _ 2 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\notag\\ &= (u _ 1 v _ 2 - u _ 2 v _ 1) (\uvec{e} _ 1 \wedge \uvec{e} _ 2) + (u _ 3 v _ 1 - u _ 1 v _ 3) (\uvec{e} _ 3 \wedge \uvec{e} _ 1) + (u _ 2 v _ 3 - u _ 3 v _ 2) (\uvec{e} _ 2 \wedge \uvec{e} _ 3) \label{wedgetensorvector}\\ \notag\\ \vec{u} \times \vec{v} &=(u _ 1, u _ 2, u _ 3) \times (v _ 1, v _ 2, v _ 3) \notag\\ &= {\red(u _ 2v _ 3 − u _ 3v _ 2)}\uvec i + {\red(−u _ 1v _ 3 + u _ 3v _ 1)}\uvec j + {\red(u _ 1v _ 2 − u _ 2v _ 1)}\uvec k\notag\\ \end{align}\]Note:

- The wedge product is a tensor, not a matrix. The wedge product of two dimension $3$ vectors has a dimension of $3$, not $9$ $\Eqn{wedgetensorvector}$.

- This matrix is anti-symmetry matrix of odd dimension and thus has a zero determinant.

However, this result is not the area of this two vectors. $U \wedge V$ is a bivector, it’s norm

\[A^2=\norm{U\wedge V}^2\substack{\small\text{numerically}\newline\huge {=}}(U \times V)^2\]is the area of the parallelogram.

Generalization as a direct way to calculate $n$-dimensional area, (specially, $3$-dimensional area being the volume): the $n$-dimensional area is defined as a $n$ wedge product of $n$-dimensional vectors. For $n=3$,

\[\vec{u} \wedge \vec{v} \wedge \vec{w} = (u _ 1 v _ 2 w _ 3 + u _ 2 v _ 3 w _ 1 + u _ 3 v _ 1 w _ 2 - u _ 1 v _ 3 w _ 2 - u _ 2 v _ 1 w _ 3 - u _ 3 v _ 2 w _ 1) (\uvec{e} _ 1 \wedge \uvec{e} _ 2 \wedge \uvec{e} _ 3)\]Again we obtain the volume ($3$-dimensional area) $V^2=\norm{\vec{u} \wedge \vec{v} \wedge \vec{w} }$.

There is more to it. While $\vec{u} \wedge \vec{v} \wedge \vec{w}$ is a simple construction of three vectors, it is also a wedge product of vector and yet a wedge product $\vec{u} \wedge (\vec{v} \wedge \vec{w}).$ The volume of the parallelepiped ($3$-dimensional area) is now the span of a vector and an parallelogram ($2$-dimensional area). Similarly, a $(n+m)$-dimensional area can be spanned by a $n$-dimensional area and $m$-dimensional area.

$p$-Forms from Wedge Product

After having gained some familiarity with wedge products, we are now ready to construct $p$-forms.

Still, wedge (楔) product (楔积) $\wedge$ is a special kind of tensor product. The rule for wedge product of basis is as follow:

\[\d x^{\mu _ 1} \wedge \d x^{\mu _ 2} \wedge\cdots\wedge \d x^{\mu _ r} = \sum _ {P\in \mathbb S _ r} \operatorname{sgn}(P) \d x ^{\mu _ {P(1)}} \otimes \d x^{\mu _ {P(2)}}\otimes \cdots\otimes \d x^{\mu _ {P(r)}} \label{r-form-basis}\]$\Eqn{r-form-basis}$ gives us the basis for $r$-forms. The space of $r$-forms spanned by these bases is denoted as $\Omega^r$. A general $r$-form is then

\[\omega=\frac{1}{r!}\omega_{\mu_1\mu_2\cdots\mu_r}\d x^{\mu _ 1} \wedge \d x^{\mu _ 2} \wedge\cdots\wedge \d x^{\mu _ r}\]There are only $\binom{m}{r}=\frac{m!}{(m-r)!r!}$ choices of $\set{\d x^{\mu_i}}$ to form a non-zero basis, so is the dimension of space $\Omega^r$.

Wedge Product of $p$-Forms

For example,

\[\begin{align} (3\d x + \d y) ∧ (\e^x\d x + 2\d y) &= 3\e^x\d x ∧ \d x + 6\d x ∧ \d y + \e^x \d y ∧ \d x + 2\d y ∧ \d y\\ &= (6 − \e^x)\d x ∧ \d y \end{align}\]Exterior Derivative

All the vector calculus, div, grad, curl, the divergence theorem and Stokes’ theorem, etc. are well defined in three-dimensional spaces. But it would be hard to generalize the notion of curl in higher dimensions.

\[\nabla \times X = \left( \frac{\partial X_3}{\partial x^2} - \frac{\partial X_2}{\partial x^3}, \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial x^3} - \frac{\partial X_3}{\partial x^1}, \frac{\partial X_2}{\partial x^1} - \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial x^2} \right),\]Exterior derivatives provide an easy way to perform vector calculus in greater-than-three dimensional spaces, with a sweet side effect that those divs, grads, curls, will be represented by two simple formulae.

Exterior Derivative of Functions

We will start from a function $f:\R^n\rightarrow \R$. We will perform an exterior derivative $\d$ on the function. Our new definition of exterior derivative should comply with normal derivatives on functions, i.e.,

\[\d f \dfdas \Partial {f}{x^1} \d x^1 + \cdots + \Partial {f}{x^n} \d x^n.\]That is a good old one-form! Or we could write it as

\[\nabla f = (\d f)^\sharp\]to emphasize the relationship between divs and exterior derivatives.

General Definition of Exterior Derivative

The exterior derivative of a function is a one-form. We will go and find out the “second derivative” of $f$.

For our definition to make sense, we require that

- The “derivative” of a $1$-form (first derivative) should result in a $2$-form.

- The “second exterior derivative” of a function should somehow relate to the second derivative of $f$.

I couldn’t find any way to introduce the definition from deductions heuristically, so I decided to give the definition firs and explain it later.

In general, the exterior derivative of a $p$-from $\omega=ω_{i_1\cdots i_p} \d x^{i_1} \wedge\cdots\wedge \d x^{i_p}$ is defined by

\[\begin{align*} \d\omega &= \d (f\, dx_{i_1} \wedge \cdots\wedge dx_{i_n} ) \\ &= \d f \wedge dx_{i_1} \wedge\cdots \wedge dx_{i_n}, \quad\text{where } \d f = \Partial {f}{x^1} \d x^1 + \cdots + \Partial {f}{x^n} \d x^n\\ &=\frac{1}{p!}\Partial{ω_{i_1\cdots i_p}}{x^i} \d x^i \wedge \d x^{i_1} \wedge\cdots\wedge \d x^{i_p} \end{align*}\]From this definition, we have

For $\omega=f$, it agrees with the differential of $f$

Exterior derivative have a Leibniz’s Rule

\[\begin{align*} \d(\omega\wedge\eta)&=(\d\omega)\wedge\eta+(-1)^p\omega\wedge(\d\eta),\quad \text{$\omega$ is $p$-form}\\ \end{align*}\]$\d^2=0$.

Proof for $\d^2=0 $:

\[\begin{align*} \d(\d\omega) &= \d (\frac{1}{p!}\Partial{ω_{i_1\cdots i_p}}{x^i}\d x^i \wedge \d x^{i_1} \wedge\cdots\wedge \d x^{i_p})\\ &=\frac{1}{p!}\d (\Partial{ω_{i_1\cdots i_p}}{x^i}\d x^i )\wedge \d x^{i_1} \wedge\cdots\wedge \d x^{i_p} \\ &=\frac{1}{p!} \Partial{^2ω_{i_1\cdots i_p}}{x^i\partial x^j}\d x^i \wedge \d x^j \wedge \d x^{i_1} \wedge\cdots\wedge \d x^{i_p} \end{align*}\]Since $\Partial{^2ω_{i_1\cdots i_p}}{x^i\partial x^j}$ is symmetric with respect to $x^i$ and $x^j$, and $\d x^i \wedge \d x^j$ is antisymmetric, the RHS is zero.

For example,

\[\begin{align*} \d (\d f) &= \d (\Partial {f}{x^1} \d x^1 + \cdots + \Partial {f}{x^n} \d x^n)\\ &=(\d \Partial {f}{x^i} )\wedge\d x ^ i + \d( \d x ^ i)\wedge\Partial {f}{x^i}\\ \xrightarrow{\d( \d x ^ i)=0}&=(\d \Partial {f}{x^i} )\wedge\d x ^ i \\ &=\Partial{^2f }{x^i\partial x ^ j}\d x ^ j \wedge\d x ^ i\\ &\equiv 0 \end{align*}\]A Glimpse of Closed Form and Exact Form

If $\d \omega = 0$, $\omega$ is called an closed from. If $\d \eta=\omega$ , $\omega$ is called a exact form. These names have something to do with cohomology, which you will find in my later posts.

$\d^2 = 0$ means that all exact forms are closed, since $\d\omega=\d^2\eta=0$. But the reserve is not always true, i.e., not all closed forms are exact.

Before I start listing examples, let’s find out what it takes for a form to be exact. The most straightforward way to proof a differential form to be exact is to find a $\eta$ such that $\d\eta=\omega$. This problem is the equivalent to solving a differential equation, which needs the definition of integral. We’ll leave the discussion to Cohomology.

Exterior Derivative and Vector Calculus

In the beginning of this section, I promised that divs, grads, curls, will be represented by two simple formulae in terms of exterior derivative. By the end of this subsection, we will have a diagram looks like this :

\[\begin{array}{ccccccc} &\text{0-forms} & \xrightarrow{\d}{} &\text{$1$-forms} & \xrightarrow{\d}{} & \text{$2$-forms} & \xrightarrow{\d}{}& \text{$3$-forms}\\ &\downarrow &&\downarrow&&\downarrow&&\downarrow \\ &\text{ {functions} } &\xrightarrow{\nabla}{} &\text{ {vector fields} } &\xrightarrow{\nabla\times}{} &\text{ {vector fields} } &\xrightarrow{\nabla\cdot}{} &\text{ {functions} }\\ & function & & divergence & & curl & & gradient \end{array}\]We already have

\[\nabla f = (\d f)^\sharp\]Curl

Now we will see how exterior derivative act on one-forms. For example,

\[\d(F \d x+G\d y +H\d z) = (\Partial{G}{x} −\Partial{F}{y})\d x\wedge \d y +(\Partial{H}{y} −\Partial{G}{z}) \d y \wedge \d z + (\Partial{F}{z} − \Partial{H}{x})\d z \wedge \d x \notag\]If we convert these two form to a vector using the rule

\[\begin{cases} \d x \wedge \d y \rightarrow \uvec z\\ \d y \wedge \d z \rightarrow \uvec x\\ \d z \wedge \d x \rightarrow \uvec y \end{cases},\]it coincides with the definition of curl.

\[\vec{\nabla} \times V = (\Partial{H}{y} − \Partial{G}{z})\uvec x + (\Partial{F}{z} − \Partial{H}{x})\uvec y + (\Partial{G}{x} − \Partial{F}{y})\uvec z\]The conversion is called a Hodge star dual, denoted as $\star$. In $d$ dimensions the “$\star$” map takes a $p$-form to a $(d − p)$-form. In our case,

\[\begin{align*} &\Bigg(\star\left((\Partial{G}{x} −\Partial{F}{y})\d x\wedge \d y + (\Partial{H}{y} −\Partial{G}{z})\d y \wedge \d z + (\Partial{F}{z} − \Partial{H}{x})\d z \wedge \d x\right)\Bigg)^\sharp\\ &=\left((\Partial{H}{y} − \Partial{G}{z})\d x + (\Partial{F}{z} − \Partial{H}{x})\d y + (\Partial{G}{x} − \Partial{F}{y})\d z\right)^\sharp\\ &=(\Partial{H}{y} − \Partial{G}{z})\uvec x + (\Partial{F}{z} − \Partial{H}{x})\uvec y + (\Partial{G}{x} − \Partial{F}{y})\uvec z. \end{align*}\]Finally, we have the rule

\[\nabla \times V = \Big(\star\big( \d(V^\flat)\big)\Big)^\sharp.\]What this complicated rule says is the following. To take the curl of a vector, first convert it to a one-from $V^\flat$, then take the exterior derivative of the one-from and get $\d V^\flat$, and finally turn the two form back to a vector through $\star \left(\phantom{a}\right)^\sharp$.

Gradient

Now we take the exterior derivative of a two-from,

\[\begin{align*} &\d (F \d y \wedge \d z + G\d z \wedge \d x + H\d x \wedge \d y)\\ & = (\Partial{F}{x}\d x + \Partial{F}{y}\d y + \Partial{F}{z}\d z) \wedge \d y \wedge \d z +(\Partial{G}{x}\d x + \Partial{G}{y}\d y + \Partial{G}{z}\d z) \wedge \d z \wedge \d x+\\ & \phantom{==}(\Partial{H}{x}\d x + \Partial{H}{y}\d y + \Partial{H}{z}\d z) \wedge \d x \wedge \d y\\ &= (\Partial{F}{x} + \Partial{G}{y} + \Partial{H}{z} )dx ∧ dy ∧ dz\quad, \end{align*}\]which looks like the gradient. The rule is again

\[\vec\nabla\cdot V = \Partial{F}{x} + \Partial{G}{y} + \Partial{H}{z}.\]Write that rule as Hodge dual, we have

\[\vec\nabla\cdot V=\star\Big(\d \big(\star (V ^\flat) \big)\Big),\]which means the following. Covert a vector field to a one-form, then take the Hodge dual of it to get a two-form, and then take the exterior derivative to get the right coefficient, and finally convert the result back to a number.

Summary

\[\begin{array}{ccccccc} &\text{0-forms} & \xrightarrow{\d}{} &\text{$1$-forms} & \xrightarrow{\d}{} & \text{$2$-forms} & \xrightarrow{\d}{}& \text{$3$-forms}\\ &\downarrow &&\downarrow&&\downarrow&&\downarrow \\ &\text{ {functions} } &\xrightarrow{\nabla}{} &\text{ {vector fields} } &\xrightarrow{\nabla\times}{} &\text{ {vector fields} } &\xrightarrow{\nabla\cdot}{} &\text{ {functions} }\\ & function & & divergence & & curl & & gradient \end{array}\]We have gone through all items in the diagram above and verified that our definition of exterior derivative united our standard definition of differential operators in vector calculus into one simple symbol $\d$.