Fiber Bundles

Posted: January 16, 2019

Edited: January 16, 2019

Status:

Paused

Tags :

Fiber

Fiber-bundles

Topology

Berry's-Phase

Categories :

Topology

Fiber Bundles

This section follows [Bohm, A. et al] and [Nakahara].

Intuition of Fiber Bundles

Generally speaking, a fiber bundle is a topological space where there are extra structures. This structure is summarized as the topological space locally looks like the direct product of two subspaces - a typical fiber and a base space.

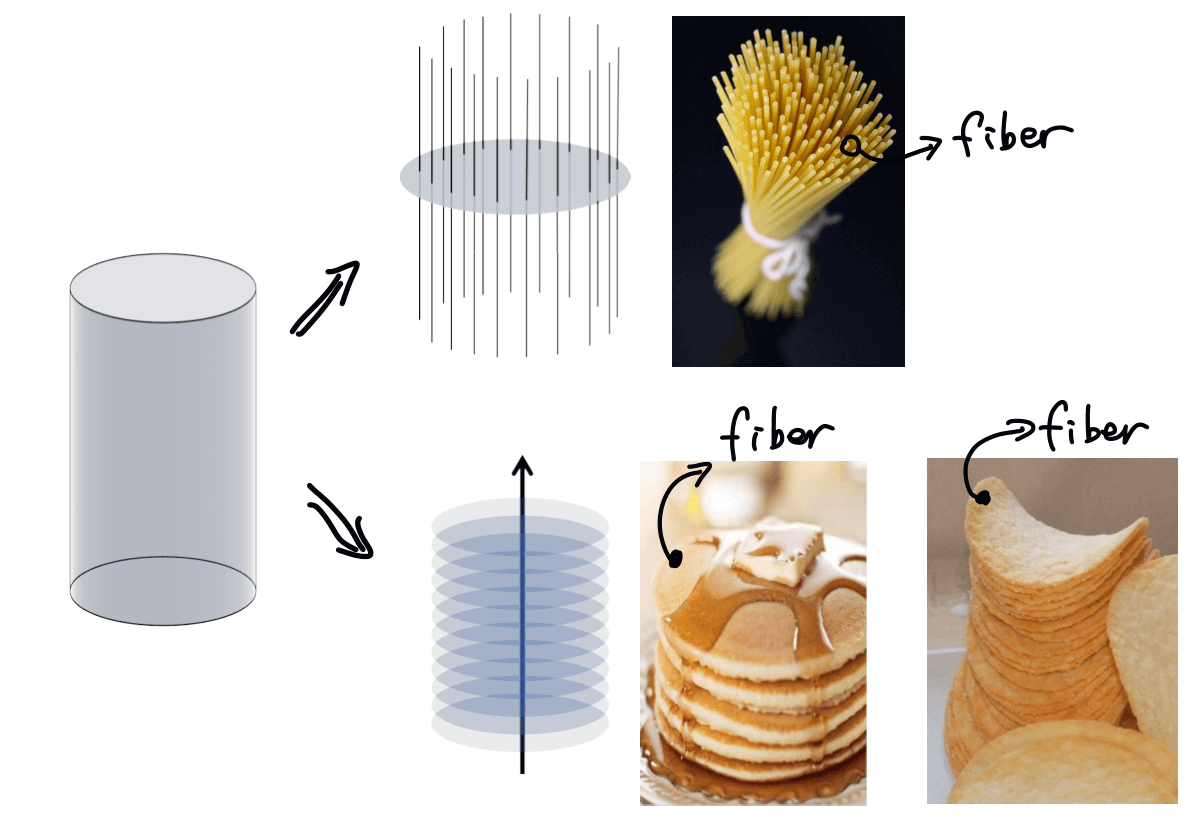

A good example of a fiber bundle is a cylinder. I think this is the most intuitive way of explaining the name. A bundle of fibers is called a fiber bundle, like a handful of pasta. However, a fiber need not be an actual “fiber”, it could also be a higher dimensional manifold, like a piece of pancake or a potato chip.

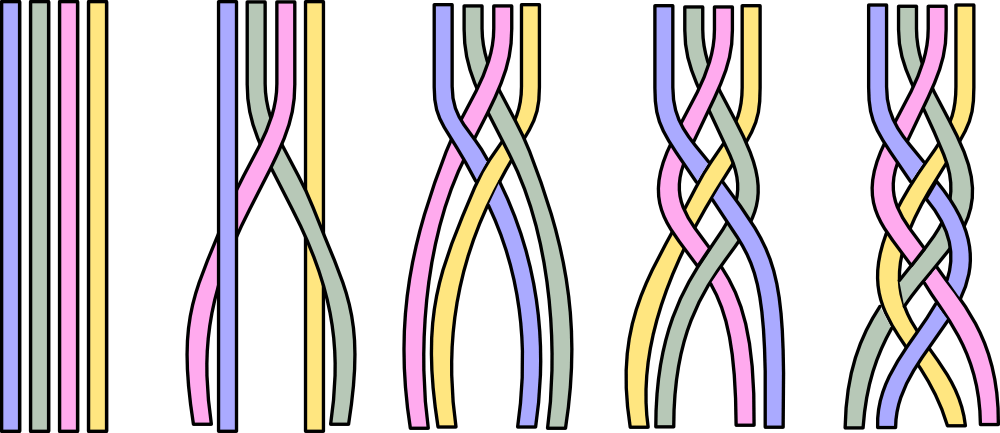

A non-trivial example of braiding is the braiding of strands.

Take a bunch of pasta for example. A fiber bundle is just like a bunch of pasta. Each piece of pasta is a fiber. All the pasta put together becomes the entire topological space which we call a fiber bundle or a total space. That pasta can be twisted and bent, but each piece of pasta is distinguishable and looks alike. And at each point of the total space (the entire bunch of pasta), it looks like a direct product of a base space and a fiber. This means two things.

- This higher dimensional total space can be reduced to lower dimensional spaces. We can ignore the additional fiber sometimes to have a good “approximation” when the effects of fibers are not strong, like when the phase of state vector can be ignored.

- A lower dimensional space can be mapped to a higher dimensional space. An extra structure can always help us understand the total space better. Also, problems considered in a higher dimensional space can sometimes give simpler expression, like in the case of Calabi-Yau space.

Examples of fiber bundles includes

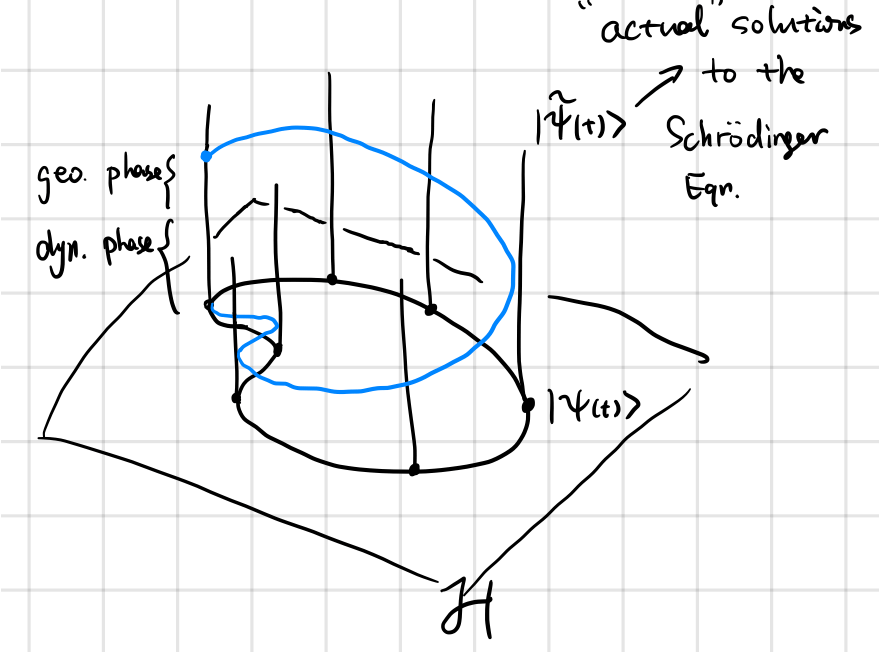

- Hilbert space in Quantum Mechanics. In Quantum Mechanics, phases are usually ignored in solutions to the Schrödinger equation. Not until Berry made the discovery of the Berry phase did the complex phase was regarded seriously, and that leads directly to topological insulators as well as quantum computations. To maintain what we have already had for quantum mechanics, we can view the complex phases as strands stemming from each point of the Hilbert space. Originally, the state vector traces out a circle during a cyclic evolution. Now when we look closer, there is an additional structure to each point of the Hilbert space, namely the phase. We found out that during a cyclic evolution, the state vector traces out a spiral. In other words, the state vectors $\ket{\psi}$ are really an equivalent classes $\set{\ket{\psi} \mid \ket{\psi}=\e^{\i \varphi} \ket{\psi _ 0} }$.

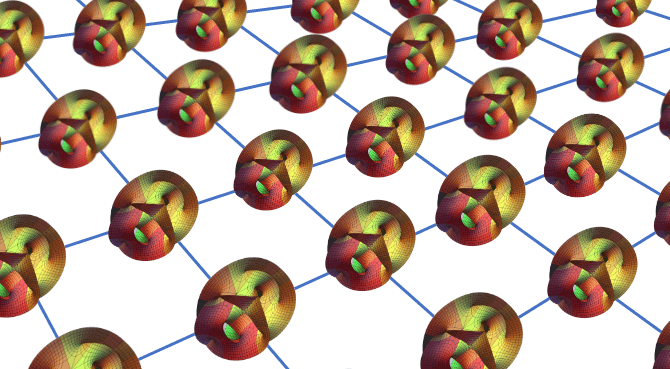

- Calabi-Yau space, picture adopted from code. A common saying is that each point of space is a Calabi-Yau space. Usually, the extra $6$ dimensional are overlooked and we are fine in our daily lives. But once we look closely enough, space reveals its additional structure.

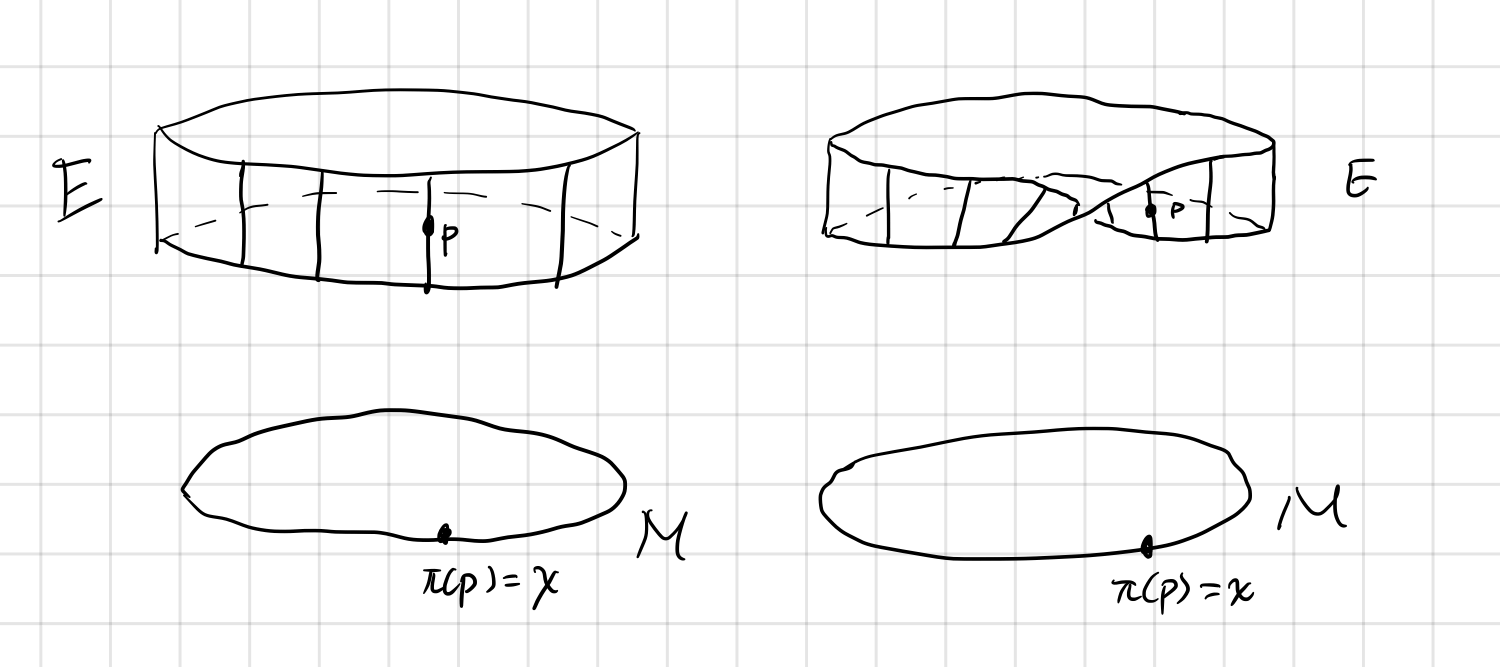

- A mathematical example of a trivial and a non-trivial example: the surface of a cylinder and a Mobius band can both be considered as fiber bundles.

Basic Definition

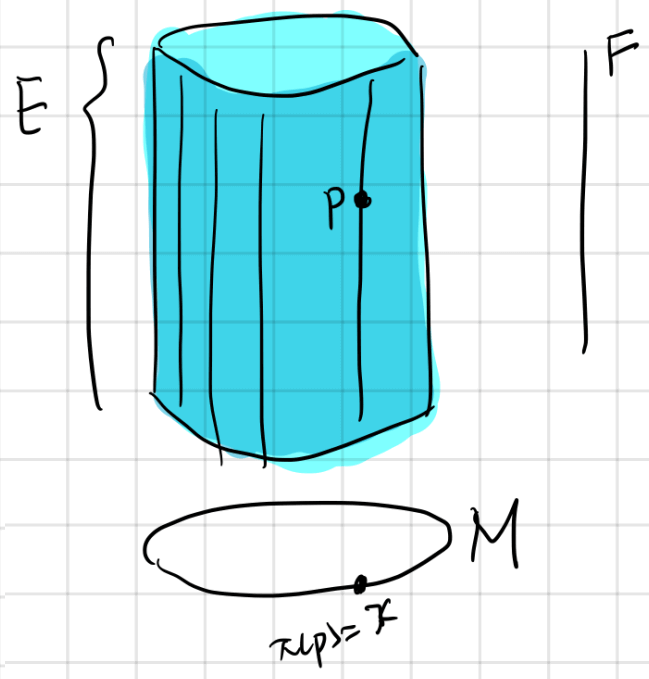

Formally, a (differentiable) fiber bundle is a triple $(E,\pi,M)$ consists of the following elements:

- A differentiable manifold $E$ called the total space.

- A differentiable manifold $M$ called the base space.

- A differentiable manifold $F$ called the fiber (or typical fiber).

- A surjection $\pi : E\rightarrow M$ called the projection. The inverse image of a point $p\in M$, $\pi^{-1}(p)$ is called the fiber $F_p\simeq F$ at point $p$.

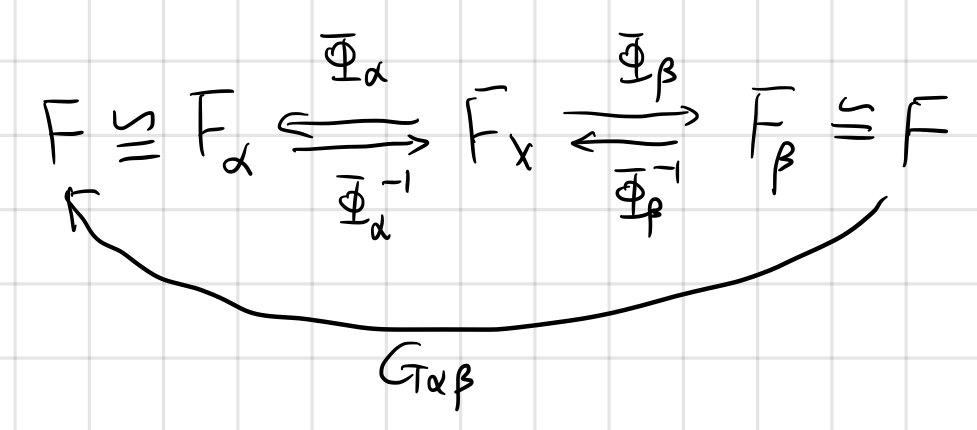

The relationships between these entities are represented by the following diagram. Notice that the base space is not a subset of the total space. It is an independent manifold “outside” of the total space. The same is true for the fiber.

In many textbooks a fiber bundle is defined as a quintuple $(E,\pi,M,G,F)$. I think it’s better to start defining as little as possible, so I chose to define it as a triple and add $G$ and transition functions later.

Additional Structures of Fiber Bundles: Transition Functions etc.

An important insight of fiber bundle is the existence of local trivializations. Namely in a small enough neighborhood of the total space, it is always possible to find a way to “decompose” the total space to the direct product of a neighborhood of base space and a typical fiber.

Interpretation of the Transition Functions and Structure Group

Short reminder of the word “Topology”:

Mathematically, a topology is defined as a family of subsets $\tau$ of a set $X$. The pair $(\tau,X)$ is called a topology. This definition is evidently related to the connectedness of the set $X$. Elements belong to the same subset are connected, otherwise they are separated. From the connectedness all topological properties are defined.

For a manifold, the topology is also represented as how the charts are glued together. Different gluing choices shows different “twisting”. For example, different gluing of triangles can form different topologies like below, image adopted from Wikipedia.

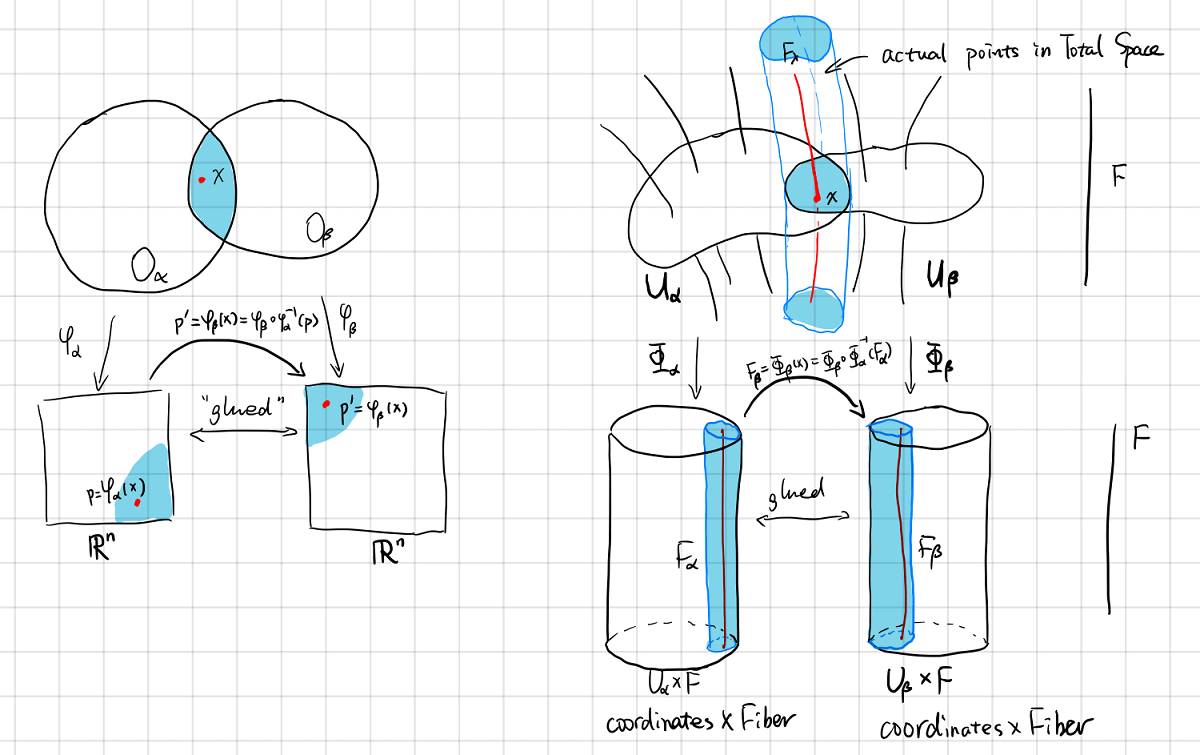

Recall that the topological aspect of a manifold is represented as how the charts are glued together. Thus the topological aspect of a fiber bundle is best represented by the transition functions.

In the following diagram, the red dots on the left are “glued” together, the red lines on the right are “glued” together.

The transition function is denoted as $G_{\alpha,\beta}$

\[G_{\alpha,\beta}(x)\dfdas\Phi_\alpha\circ\Phi_\beta^{-1}(x): F_\alpha\rightarrow F_\beta,\quad \forall x \in U_\alpha \cap U_\beta\]Since the fibers $F_\alpha$ and $F_\beta$ are diffeomorphic to typical fiber $F$, $G_{\alpha,\beta}$ is a map from $F$ to $F $ itself.

The transition function actually forms a group under composition

\[\begin{align*} \id &=G_{\alpha,\alpha} & \text{Identity}\\ G_{\alpha,\beta}^{-1}&=G_{\beta,\alpha} & \text{Inverse}\\ G_{\alpha,\beta}\circ G_{\beta,\gamma}&=G_{\alpha,\beta} & \text{Closure}\\ (G_{\alpha,\beta}\circ G_{\beta,\gamma})\circ G_{\gamma,\delta}&=G_{\alpha,\beta}\circ (G_{\beta,\gamma}\circ G_{\gamma,\delta}) & \text{Associativity} \end{align*}\]This group is called the structure group $G$ of the bundle $F$. We call the action $G_{\alpha,\beta}(x)F_\alpha=F_\beta$ as “$G$ act on $F$ on the left”.

Principal Fiber Bundle

There is a special kind of bundle called the principal bundle, where all the fibers are isomorphic to the structure group $G$.

A piece of fiber is essentially a topological space, and you can add a group structure to the space such that group properties (identity, inverse, closure, and associativity) are endowed. If the group structure is the same as structure group, we will call this fiber bundle a principal fiber bundle.

Is it possible to make every fiber bundle a principal fiber bundle? If not, how can we be sure that it is not possible?

Connections on Fiber Bundle

This section follows Peter Szekeres.

Linear Connections

There is no natural way of comparing tangent vectors $V_p$ and $V_q$ at $p$ and $q$, for if they had identical components in one coordinate system this will not generally be true in a different coordinate chart covering the two points.

Consider the coordinate transformation: