Lie Groups and "Actions"

Posted: January 12, 2019

Edited: March 26, 2019

Status:

Completed

This post requires some level of understanding of Lie groups. This post is more like a proposal of reorganized material for learning Lie group and Lie algebra, rather than a detailed study note.

For self-studying, I recommend [Bohm et al.], [Sudarshan et al.] and a YouTube open course [Frederic Schuller’s Lectures on Geometrical Anatomy of Theoretical Physics] for Physics students, and for those who want more mathematical insights, I recommend [Michael L. Geis] (for undergrads), [Brian C Hall] and [Alexander Kirillov, Jr] (can be found here. This book requires some understanding of topology).

This post is based on sources listed above. Some of the proofs also come from [Solutions for Nakahara].

Here is the structure of this series of posts:

graph TB subgraph Lie Group as Differential Manifold A[Xe] -->|left action|B[Left invar. <br>vector field X] B -->|start from <i>g</i>| C[curve Γ] C -->|proven to be|D[Exponential map] end subgraph Lie Algebra as Generator A -->|belongs to|E[TeG] E -->|uses|D D -->|generates|F[Small region near <i>e</i>] end subgraph Lie group as Actions G[element as <br/> action] -->|push forward|H[Lg*] B---H end

Lie Group

Roughly speaking, a Lie group is a continuous group. The elements in this group are continuous, and the group operations are continuous.

Formally, a Lie group $(G,\cdot)$ is a differentiable manifold with a group structure such that the operations

- $\cdot : G\times G \rightarrow G,\, (g _ 1,g _ 2)\mapsto g _ 1\cdot g _ 2$

- $^{-1}: G\rightarrow G,\, g\mapsto g^{-1}$.

are differentiable.

Lie Groups’ Actions

Back Story

After writing down this subsection, I realized that I could have summarized the entirety of it as “A group element’s action needs to be properly defined to avoid such confusions as ‘A group element can act on other elements in the group, but an element should be an action on external entities’ like I had for a long time.”

A group is interpreted in an introductory level, a collection of actions that preserve symmetries. This action is often defined via an external imaginary object, such as a cube or a sphere. Multiplication of group elements is interpreted as a consecutive application of these actions on the aforementioned object, which is considered a rigid body and can have coordinates in Euclidean space. The group elements are now regarded as actions on coordinates, which is conveniently represented by matrices. Such is the linear representation of groups. So far so good.

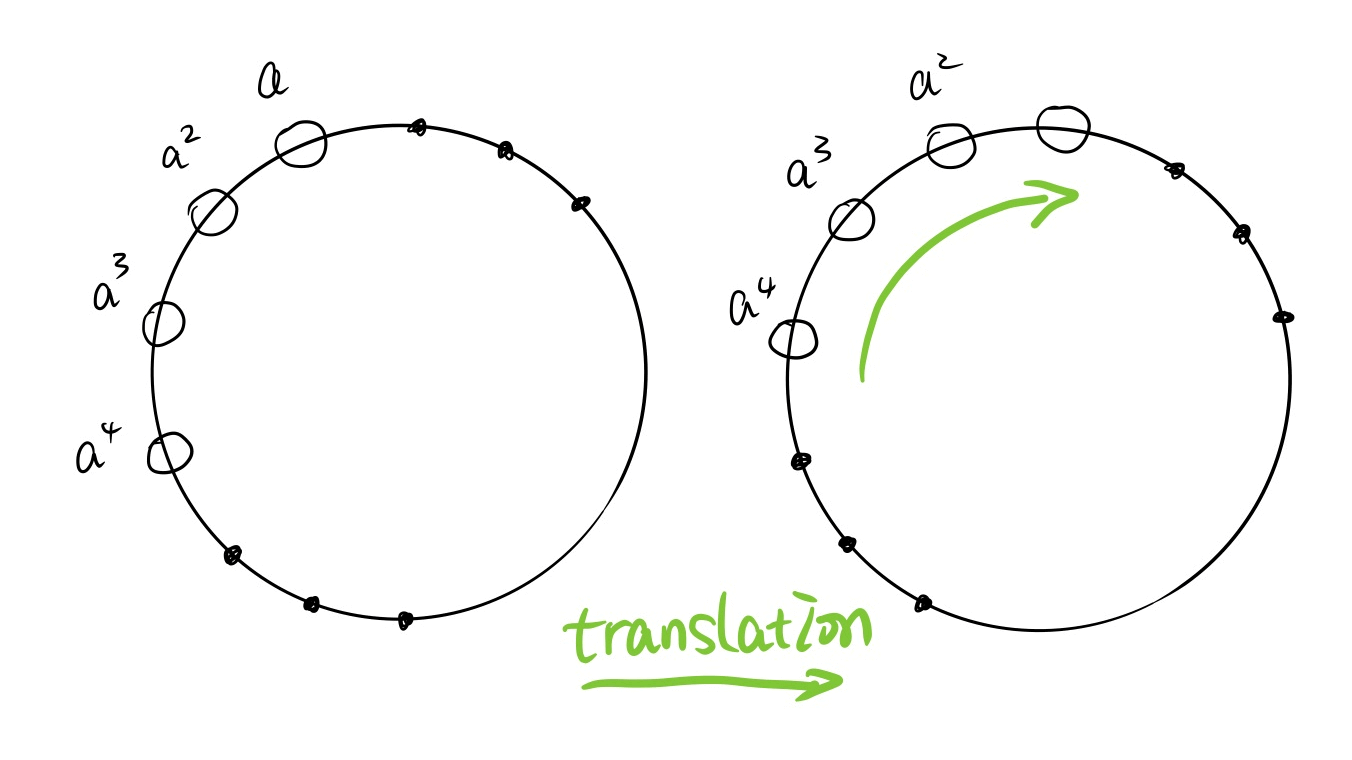

When the cyclic group was introduced, so was the left or right translation, defined as taking one element out and multiply it with every element of the group. This operation when viewed (and called) as a translation. Considering that cyclic groups often represent “rotations”, the translation is often depicted as follow. The fact that an element (which is a rotation) acting on the group “rotates” the group, is often neglected, or considered as a trivial coincidence since there is no “action on a group” defined. So far so good.

Then a more mathematical way of defining a group is introduced. Multiplication with a bunch of properties (namely closure, associativity, identity and invertibility) is defined on a set, making it a group. There is really not much to say about what is in this set. For all one knows, it’s like a point set, with each point representing “something” like an action. This point of view is validified when one learned that $\set{ \e^{\i 2\pi j/ N} \mid j=1,2,3,\cdots, N}$ is a perfect cyclic group under multiplication of numbers. So far so good.

By taking the mathematical highroad, the external “rigid body” is removed. Previously we need two parts to define a group; one is the set of “actions”, the other is something “to be acted”. The former can be represented as matrices, the latter a set of coordinates. It makes no sense saying that a matrix “rotates another matrix $\frac{\pi}{6}$ around $x$-axis”. When faced with such discrepancy, I thought that the naïve view of groups as point sets must be wrong. Groups must be made of something much more complicated than matrices, let along points since the group elements can somehow act on each other as well as on other entities.

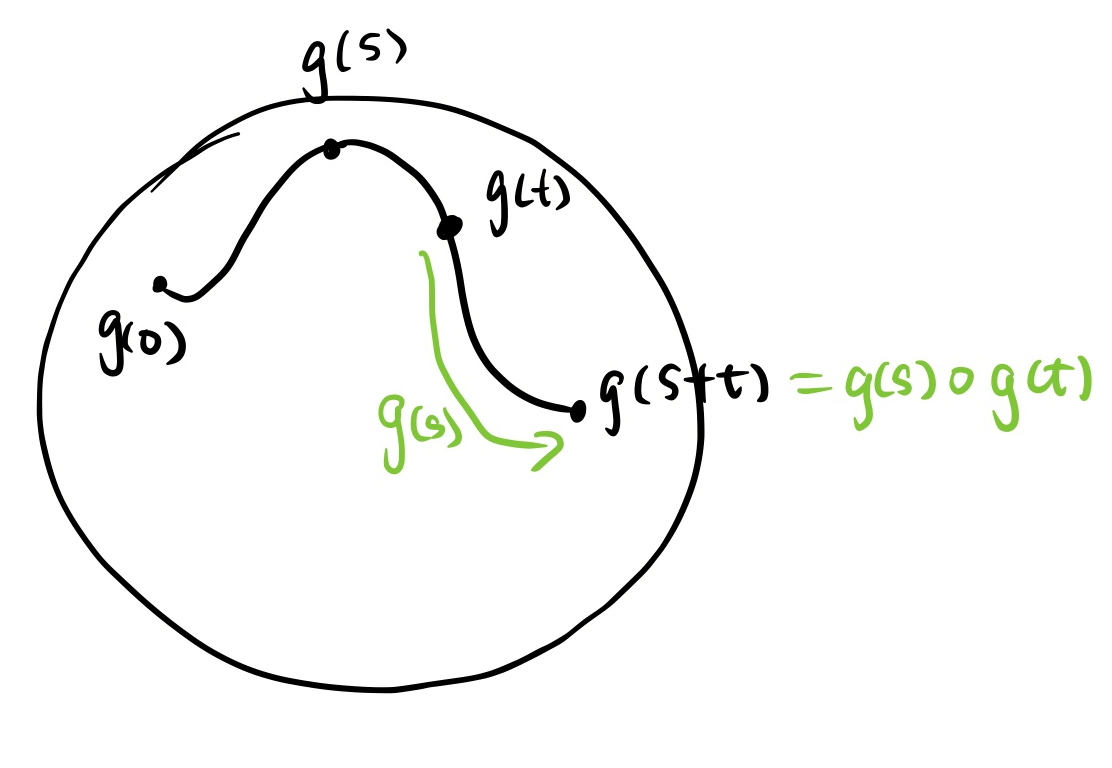

Thing got out of hand when I encountered Lie group. Similar to discrete groups, I first learned that continuous operations such a translation and rotations are represented by Lie groups. So a Lie group is made of continuous operations (often considered acting on a sphere). Then I learned formally; a Lie group is defined as a smooth manifold equipped with smooth group operations, which clearly means that a Lie group is made of points! Then there is the concept of left and right translations, depicted as magical translations along the one-parameter subgroups. $g(s)\circ g(t)$ is understood as $g(s)$ as a action acting on the point $g(t)$, moving it to a new point $g(s+t)=g(s)\circ g(t)$.

The confusing property that a group element can act on the group itself is caused by lack of proper definition of “action” of a group element. This chapter is often organized at the end of Lie group, but I think that early exposure to this concept helps to reduce the aforementioned confusion.

Lie Groups’ Actions on Manifold

A left $G$-action of a Lie group $(G,\cdot)$ on a manifold $ M$ is a binary operation $(\slot,\slot)$ sometimes denoted as $\triangleright$.

\[G\times M \rightarrow M: (g,p)\mapsto g\lact p\]such that

\[\begin{align*} e\lact p &= p,\\ g _ 1 \lact \left(g _ 2 \lact p\right) &= \left(g _ 2\cdot g _ 1\right)\lact p. \end{align*}\]Sometimes a dot “$\,\cdot\,$” is abused to denote this left action as $g\cdot p$ when there is no ambiguity about which operation to be used.

In a similar fashion, a right $G$-action $\ract$ is defined as

\[M \times G \rightarrow M : (p,g)\mapsto p\ract g\]such that

\[\begin{align*} p\ract e &= p,\\ \left(p \ract g _ 2\right)\ract g _ 1 &= p \ract \left(g _ 1 \cdot g _ 2\right) . \end{align*}\]Lie Group’s Actions on Itself

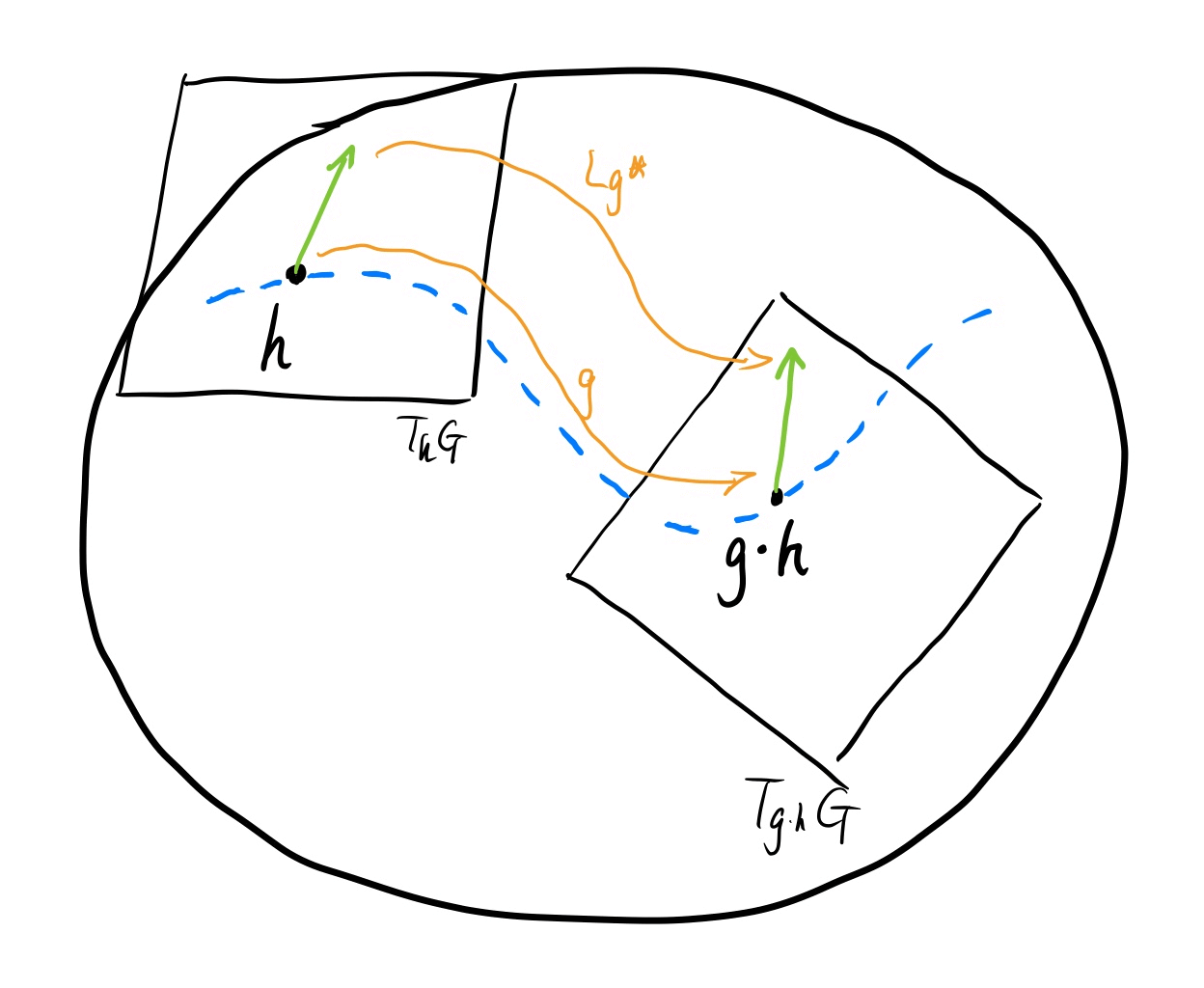

Notice that Lie group itself is a manifold, on which Lie group can thus “act”. The left action or left translation: $L _ g: G\rightarrow G$ is defined by $L _ g(h)=g\cdot h$. Written in the form of left $G$-action on itself, it reads:

\[\begin{align*} &G \times G \rightarrow G: &L _ g(h) \mapsto g \lact h \dfdas g\cdot h \in G \end{align*}\]Similarly, Right action or right translation $R _ g : G\rightarrow G$ is defined by $R _ g(h) = h\cdot g$.

Lie Group’s Actions: Pushed Forward

Vectors Are Pushed Forward

This section follows [Bohm, A. et al].

Let $M _ 1$ and $M _ 2$ be smooth manifolds, $p\in M _ 1$ and $\varphi: M _ 1\rightarrow M _ 2$ be a smooth function. Then $\varphi$ induces a linear map

\[\varphi _ * : T _ p M _ 1 \rightarrow T _ {\varphi(p)}M _ 2\]celled the pushforward or the differential map. This map is described by considering an arbitrary tangent vector $v _ p\in T _ p M$ to a curve $C _ 1:[0,1]\rightarrow M _ 1$, i.e., $v _ p = \Big.\D{C _ 1}{t}\Big\vert _ {t=0}$. The image of $C _ 1$ is a smooth curve in $M _ 2$ under $\varphi$:

\[C _ 2\dfdas\varphi\circ C _ 1: [0,1]\rightarrow M _ 2\]The push forward of a vector is then

\[\varphi _ * (v _ p)=v _ {*p} \dfdas \Big.\D{C _ 2}{t}\Big\vert _ {t=0}\]*Differential Forms Are Pulled Back

This section follows [Bohm, A. et al].

Left $M _ 1$ and $M _ 2$ be smooth manifolds, $p\in M _ 1$ and $\varphi: M _ 1\rightarrow M _ 2$ be a smooth function. Then $\varphi$ induces a linear map between cotangent spaces,

\[\varphi ^ * : T _ p^* M _ 1 \leftarrow T _ {\varphi(p)}^*M _ 2,\]called the pullback map. This map is described by considering an arbitrary cotangent vector $\omega _ {\varphi(p)}$ at $T _ {\varphi(p)}^*M$. The pullback is defined as its action on an arbitrary element $u _ p$ of $T _ pM$. We have

\[\big[\varphi^*(\omega _ {\varphi(p)})\big](v _ p)=\omega^* _ {\varphi(p)}(u _ p)\dfdas \omega _ {\varphi(p)}(v _ {*p})\]where the RHS only contains quantities we have defined.

Push Forward of Left and Right Actions

Each of these actions also defines the action of $G$ on vector fields as well as differential forms on $G$ (as a manifold). For a tangent vector $v ∈ T _ hG$ at $h\in G$, the push forward of left action $(L _ g) _ ∗$ will move the vector to $T _ {g\cdot h} G$. This map is denoted as

\[(L _ g) _ *: T _ gG\ni v\mapsto (L _ g) _ * v\in T _ {g\cdot m}.\]Sometimes the notion of a dot “$\,\cdot\,$” is again abused to denoted such action as $g\cdot v = (L _ g) _ *v$.

In short, the left action $L _ g$ carries everything defined on $h$ to $g\cdot h$ like a simple translation.

The vector field $X$ on $G$ can be thus pushed forward to another vector field ${L _ g}^* X$:

\[({L _ g}^* X) _ {gh}\dfdas {L _ g}^* (X _ h)\]Lie Group’s (Matrix) Representations

The idea of relating a Lie group to a set of action is closely related to the notion of representation. When we choose to make Lie group act on a Euclidean space, the transformation can be described by a matrix. In other words, a one-to-one correspondence can be established between a Lie group and a set of matrices.

Representation of Lie Groups

A Lie group $G$ can act on a Manifold $M$, denoted as the “action” map:

\[\begin{array}{cccccccc} G & \times & M & \rightarrow & M \\ \text{A Lie group} & \text{acts on} & \text{a manifold} & \text{gets} & \text{the same amnifold} \\\\ (\quad g & \cdot & m\quad ) &\mapsto & m'\dfdas(gm)\\ \substack{\text{An element in}\newline \text{Lie group}} & \text{acts on} & \substack{\text{a point in}\newline \text{manifold}} & \text{gets} & \substack{\text{another point in}\newline \text{manifold}} \\ \Updownarrow & & & & {\color{red}\textbf{same}}\Updownarrow \\ (\quad\rho(g) & \cdot & m\quad ) &\mapsto & m'\dfdas(\rho(g)m)\\ \substack{\text{A map $\rho$}\newline \text{depend on $g$}} & \text{acts on} & \substack{\text{a point in}\newline \text{manifold}} & \text{gets} & \substack{\text{another point in}\newline \text{manifold}} \\ \end{array}\]The same “action” map can be replaced my a map $\rho$ that is chosen to be the same at every point on $M$. Such replacement is called the representation on the representation space $M$, or a representation in short. That is to say, the action of a Lie group on a manifold is nothing but a map. This map is represented by another map $\rho$.

\[\begin{array}{cccccccc} g &&& & m'\dfdas(gm)\\ \substack{\text{An element in}\newline \text{Lie group}}&& \Huge\circlearrowleft& & \substack{\text{another point in}\newline \text{manifold}} \\ \downarrow \scriptsize\text{maps to} & & \text{circles around} & & \uparrow \\ \rho(g) & \cdot & m &\mapsto & m'\dfdas(\rho(g)m)\\ \substack{\text{A map $\rho$}\newline \text{depend on $g$}} & \text{acts on} & \substack{\text{a point in}\newline \text{manifold}} & \text{gets} & \substack{\text{another point in}\newline \text{manifold}} \\ \end{array}\]Notice that the map $\rho$ need to satisfy the following conditions:

\[\rho(g) m_0 = g\cdot m_0, \quad\text{for all } g\in G\\ \rho(g_0) m = g_0 \cdot m, \quad\text{for all } m\in M\\\]hence such map $\rho$ does reflect the properties of Lie group, which is why representation theories are so important in group theory.

Matrix Representations

Recall that a manifold always have local coordinates. Therefore, any manifold can be considered locally as a Euclidean space, which means that the map $\rho$ can be viewed as matrices. Such representations are called linear representations.

Adjoint Representations

For an arbitrary Lie group, to give its representation (or more precisely, representation on the representation space $M$), a manifold $M$ must be chosen. This can be quite troublesome. Say I chose $M=\set{0}$, then the representation of any Lie group is identity map $\rho(g)=\id,\, \forall g\in G$. Such representation is too trivial to reveal anything insightful about the Lie group. Even if I choose a more complicated manifold, it’s still hard for me to make sure that $M$ not any bigger, not any smaller, that such choice is “just right”.

Remember that Lie group itself is a manifold and can thus acted on. What choice is better than $G$ itself? Such representation is $M$-independent, and can provide information on $G$ “just right”.

\[\begin{array}{cccccccc} G & \times & G & \rightarrow & G \\ \text{A Lie group} & \text{acts on} & \substack{\text{Lie group itself}\newline \text{seen as a manifold}} & \text{gets} & \text{the same Lie group} \\\\ (\quad g_1 & \cdot & g_2 \quad)&\mapsto & g_3'\dfdas(g_1g_2)\\ \substack{\text{An element in}\newline \text{Lie group}} & \text{acts on} & \substack{\text{another element in Lie group}\newline \text{seen as a point in a manifold}} & \text{gets} & \substack{\text{yet another element in Lie group}\newline \text{seen as a point in a manifold}} \\ \Updownarrow & & & & {\color{red}\textbf{same}}\Updownarrow \\ (\quad\rho(g_1) & \cdot & g_2\quad) &\mapsto & g_3'\dfdas(\rho(g_1)\cdot g_2)\\ \substack{\text{A map $\rho$}\newline \text{depend on $g_1$}} & \text{acts on} & \substack{\text{another element in Lie group}\newline \text{seen as a point in a manifold}} & \text{gets} & \substack{\text{yet another element in Lie group}\newline \text{seen as a point in a manifold}} \end{array}\]